As the specter of war with imperial Japan loomed in the late 1930s, Fort Ward was reactivated as Naval Radio Station Bainbridge and the old Coast Artillery Corps gymnasium/post exchange was repurposed as “Station S” – a top secret listening station to monitor communications from the Pacific.

The building was filled with high-powered radio receivers, where radiomen – in beginning in 1945, WAVES radiowomen – intercepted coded military and diplomatic signals, copied the code groups and sent them by teletype to Washington DC for decoding and analysis. The messages were plucked from the air by an antenna field in the parade ground across the street.

In early December 1941, Station S intercepted the famous 14-part message from Tokyo to the Japanese ambassador in the top-secret “Purple” code, saying Japan was breaking off diplomatic relations with the U.S. The last part of the communique, intercepted at 1:28 am on Dec. 7, 1941, instructed the Japanese ambassador in Washington DC to deliver this message to the U.S. Secretary of State at precisely 1pm December 7, East Coast time.

Station S didn’t have a “Purple” machine to decode the message. But because it was in Japan’s most top-secret code, it was clearly very important and so was relayed immediately by teletype to the Navy Department in Washington DC.

The message didn’t announce that the attack on Pearl Harbor was imminent, but its meaning became clear a few hours later.

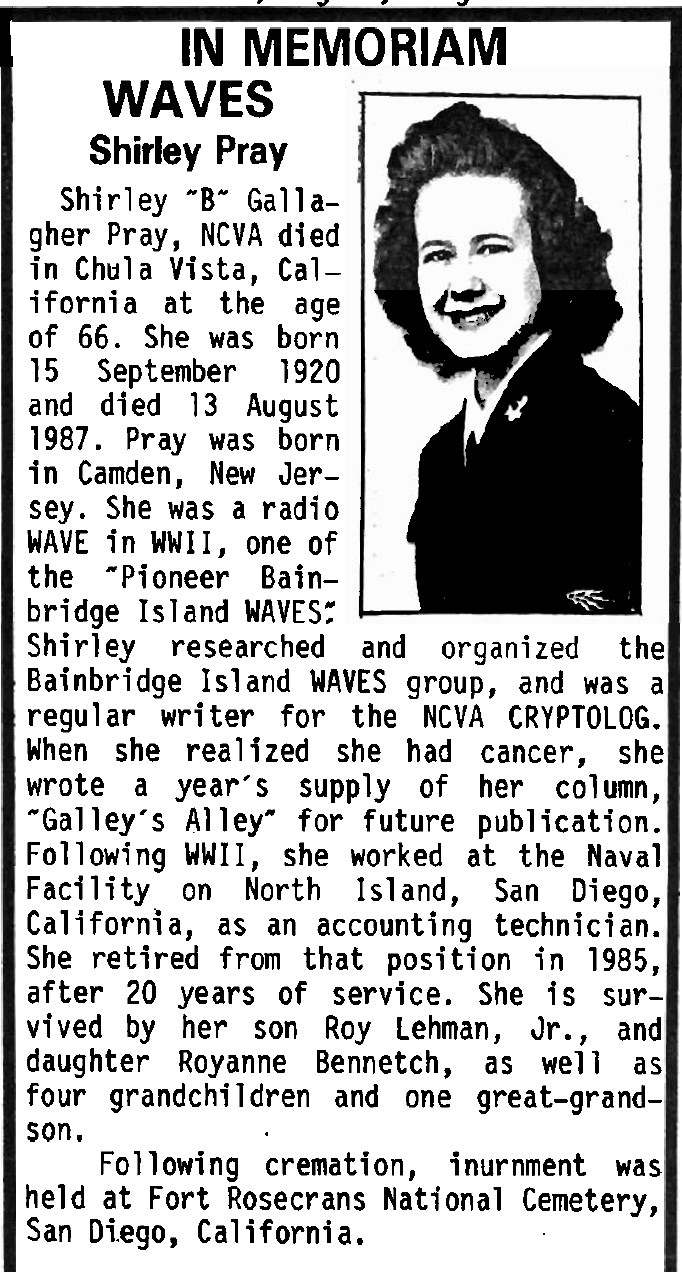

WAVES serve at Fort Ward

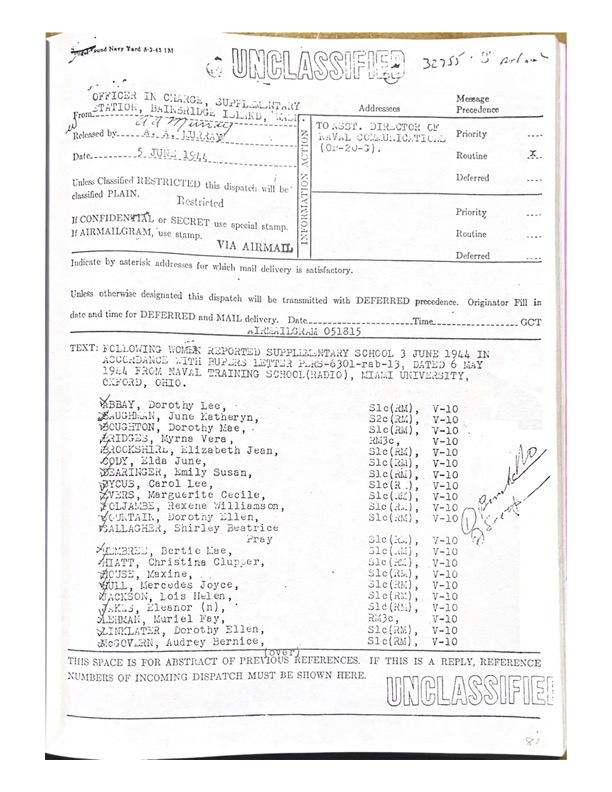

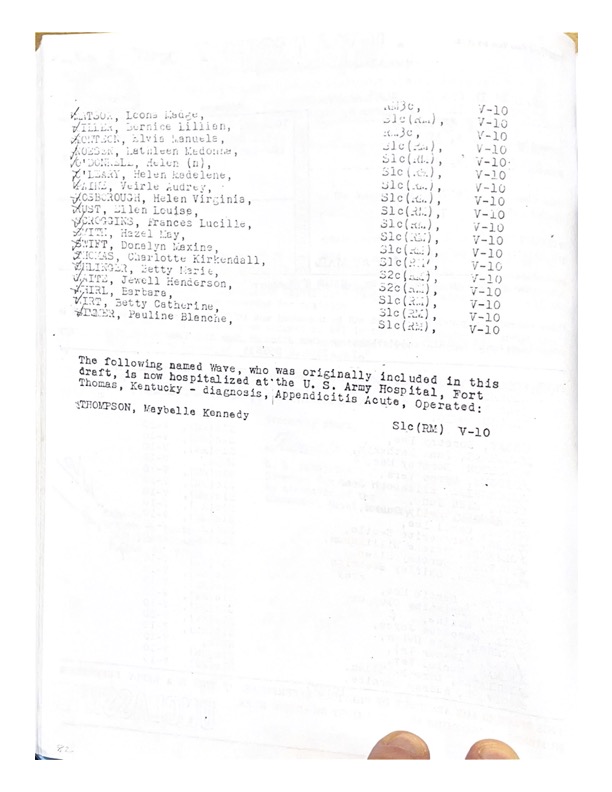

On June 5, 1944, the “Pioneer WAVES” reported for duty at Naval Radio Station Bainbridge Island, Fort Ward. So called because they were the first group of WAVES to be deployed for service in top-secret radio work, came to Bainbridge Island straight from Oxford College at Miami, OH, where they had just undergone four months of training in Morse code and other aspects of radio communications. The 39 WAVES then underwent four months of specialized training at Fort Ward, in former guardhouse and other buildings constructed nearby. In early 1945, the women took up their posts at top-secret Station S up the street, eavesdropping on enemy communications from the Pacific.

Echoes from Fort Ward history

From the archives:

“BAINBRIDGE ISLAND’S PIONEER WAVES”

By Shirley Pray (Formerly S.B.P. Gallagher)

National Cryptologic Veterans Association, 1985

The many years past have changed a very short time of their lives into a many splendored remembrance. What seemed a drag to many of them then, is recalled today as a “blast.”

Most of those women now think of those long ago few years as a privileged interval in their lives. However, the “duration and six months” length of service demand hung heavy over their heads, There were no clues as to how many years it would take to win the war, or for that matter, if the allies would win. They sometimes fretted, “There must be an easier way to end the war.” They didn’t talk too often about worldwide hostilities even though, without exception, patriotism was a paramount reason for their joining the WAVES. Life was unique they’d formed lasting friendships and they’d adjusted well to the privileged duty they’d been ordered to. duty.

They griped about their rivileged/Lnd about everything else. When reminded, “You weren’t drafted”, they griped about that too. “Nobody drafted you”, acted as a constant reminder of their status as low “man” on the totem pole. At times, that taunt hurt their ego–but not for long: They knew they were the first women of their specialty in the organization and also knew their only reason for being there was to “help win the war:”

Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES) was snuffed out of existence in accordance with Public Law 625–Women’s Armed Services Integration Act– 30 July 1948. That law has not erased the patriotism and excellent work record of every honorably discharged WWII WAVE volunteer. It has, however graphically and legally proven women’s value and worth to the Navy prior to 1948 and after.

In 1943, the Waves specifically written of here, had answered the patriotic call of their country and “joined the Navy to send a man to sea.” Late in 1943, those women who served as a small pioneer group of Waves were, via Navy logistics, first tied together (without their knowledge) at Boot Camp, Hunter College, Bronx, New York. They didn’t know that among the thousands of women at Boot Camp, a minute percentage of them would later become the first women sailors to go to Radio School at Bainbridge Island, Washington State. Had they been asked to volunteer for such a privilege one wonders now how many of them would have done so.. Bainbridge Island duty afforded those Waves, by July, 1944, an uncommon pioneer existence.

However, in December of 1943, many of those future Bainbridge Island Waves pondered the awesome spectacle of thousands of women at one time passing in review at Hunter College Boot Camp … We should remember it was a time when many young people hadn’t traveled over a ninety mile radius from their homes, and certainly not many, if any, had ever before seen so many women gathered together in one place at one time.

That great multitude of women at Boot Camp spent their first Christmas Eve in the Navy, 24 December 1943, sitting on the seats and deck at a nearby arena. There had been an alert: German sub or air attack probability, they heard later. Shortly after “lights out” the women had been rousted out of their bunks, into their overcoats and shoes and marched in the freezing cold to the Bronx Armory. No explanation at rousting, of course!

They were commanded by Section Leaders to remain silent or whisper only when necessary while in the Armory.

Those Wave Boots had never been in that building before and its darkened vastness sheltering so many souls brought the danger their country was in, clearly into focus. That lonely, silent Christmas Eve vigil produced a few quiet sobs during the many hours they huddled there in the dark. However, their esprit de corps and the dicipline they’d already learned well, kept them from giving in to their heartache and fear. Shortly before reveille they were rousted out again and marched back to their quarters where they had just enough time to get the next day’s busy Christmas Day started.

After graduation from six short weeks of training some of the women were detained at Boot Camp and were told to stand-by and wait for orders. They were glad not to be involved in the fully packed hustle-bustle of daily Boot Camp life for a day or two.

Several of the women who had requested Radio School and were told it was closed, were shocked when they learned that sixty. Waves would be going, (where else?) to Radio School. In the beginning, where that School was, remained a mystery. Their being sent to basic Radio School was the second event in their Navy life that narrowed the path that sent forty of them to Bainbridge Island. It was an indelible and proven path they forged for the many Waves that were to follow in their footsteps.

Those sixty Boot Waves, were transported to their next duty station by “troop train.” Their trip lasted four days and they wondered which end of the world they were being shanghied to. They were shunted off the main railroad tracks for long waits and afterward hurried onward mile after mile, only to wait again and again. Shortly before they arrived at their destination they were told . they were going to the Radio School at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio and that their four day trip from New York to Ohio would soon be over. Not long after leaving New York, the women were told to keep the shades of their cars down at all times on account civilians were not allowed to know of troop movements and also because of “black-out” regulations. Those women had learned early on, “ours is not to question why, ours is but to etc, etc, etc.” But still it was difficult not to question why the men milled around outside at every stop. The Dining Car and Caboose were always placed next to the Waves cars so non-frateelzation from N.Y. to Ohio was easily taken care of by the Wave Officer-in-Charge assisted by the.Porter.

After the women arrived at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio they did their radio thing to the hilt. They endured or enjoyed, as each woman believed, the rigors of being constantly overseen for four hours each day at Code; two hours a day at Typing; one hour a day Procedure; and one hour a day Theory – four months five days a week. Plus tcontinuous marching in formation by sections to class and even to the movies i in town, once a week. At Radio School they were joined by thirty-one women Marines also training as Radio Operators and they learned first hand some of the diciplines of the other women’s services personnel. All hands were allowed Port after inspection and Starboard week-end libert unle -ss they broke one of the hundreds of rules, and they libertied into Oxford, Hamilton, or Cincinnati, Ohio. They frequently griped about their “slavery” during those long months in Ohio.

While at basic Radio School they became an integral part of the Navy. During their training, without consciously knowing it, they had completely discarded their civilian ways. As a group they became the polished diciplined product the Navy demanded and produced in those days. When they completed Radio School and Boot Camp had become ancient history, those sixty women were pared down again with twenty. Waves going to the east coast and forty being ordered to Bainbridge Island, Washington State. No mention of another school in their orders. Just Navy Radio Station.

At that time most of those women couldn’t even remember the name of the capitol of Washington let alone know where Bainbridge Island was. They were given an official diversion in the form of seven days leave so any mental conflict concerning their next station was shelved.

They left Ohio for their various leave destinations secure in the knowledge they were at long last finished with school and ready for work. While at home their families said that they and their families had been investigated, in depth, by the Navy. The women accepted this fact as a routine matter. Their orders commanded their appearance at their next Duty Station on a long forgotten June, 1944 date.

On the appointed day they straggled by ones and twos into Seattle, found the Black Ball Ferry Line and boarded the ferry for their firstof many, time consuming ferry rides to Bainbridge Island. The day was overcast as usual but the view to the uninitiated was breath taking.

They learned later that each scheduled ferry was met by a Navy bus, with the male bus driver taking the long winding tree enshrouded road from the Puget Sound to the highest point on the island each and every time two or more Waves boarded the bus. An obvious caution for the driver or the women, no one ever learned which.

At days end the first Bainbridge Island Waves were in their barracks on the hill, aboard a Radio Station of hundreds of uniformed men. The men seemed a strange mix to those first women,who were not prepared to understand the numerous rates and catagories of personnel required to staff a working Navy facility. Some of the women were alarmed and concerned about such male dominance. It had never occured to any of those young women that there would be no other Waves aboard the Radio Station.

It became increasingly evident as the women took their places at B.I. that the male officers of the outfit were not accustomed to dealing with a group of young women. At times the efforts of those men seemed, to those first Waves, to border hysteria. But the women knew their place and did what they could to make it easy on themselves and the men chosen to lead them.

The Navy had hurried a female civilian employee (one of three or four who worked atput didn’t live aboard ) the base) out of the shack, into an Ensign’s uniform and into those first Wave’s lives. Her efforts did buffer the many problems that had to be resolved for women at a non-integrated base.

None of those Waves will ever forget the indolination the Commanding Officer, Doctor, Chaplain and the Training Officer proferred to them. They, who’d heard it all outspokenly at Boot Camp and at Radio School from women, heard it all again but falteringly and self-consciously from men. The women really tried after that indoctrination to help those uninitiated male leaders to lead them.

But–they never learned how to teach their Training Officer to march them in formation. Each try at the field turned into a fiasco. The women somehow couldn’t adjust to his kind of male cadence after six months strict and continuous training from female Section Leaders. And too, their Training Officer was an old Navy “salt” marching to a very different drummer.

During the final phase of their Bainbridge Island indoctrination those first Waves were told they’d been selected for the work they were to do. The gravity of their silence was clearly defined. They were also told they would be privileged to observe at first hand a phenomena that might be lost to or overlooked by the many women to follow. They were told they would actually release men directly to overseas from the school and the shack.And, after only four more months of schooling would work with some of the men returned from overseas duty where they’d suffered and served in the Pacific for years before and after 7 December 1941.

Those first women sensed the annoyance of the men it was said they were to replace. They were the only enlisted Waves at Bainbridge Island for a long time and it was obvious to the men that they were the first of the women who would “send men overseas “from B. I.

Prior to completing school and before going on watch, three of the first forty Waves were transferred to Naval Stations near their homes. Their transers seemed to be due to various obscure inabilities to adjust to the demands and restrictions of four months of intense and secret training. There also was, of course, that overwhelming majority of men: Another Wave to be transerred was restored to the organization and completed her schooling with a later class. The fifth Wave to leave Bainbridge Island received a Medical Discharge honorably. The original group of Waves were taken for granted and reminded over and over that they weren’t drafted. But they shrugged their shoulders and let such remarks roll off their backs like water off a duck. At the pre-planned time they took their places on watch at the shack. They had survived, as would the many Waves to follow, nine months intensive and continuous Navy schooling. They had also carried on in spite of the growing pains of change at USNRS, Bainbridge Island, and the loss to them of four of their ship-mates.

That first group of Waves (Class 38) resolved to and worked hard at, making the next group of Waves to arrive feel welcomed, wanted, and at ease in their new clandestine environment. Those first women knew all too well how the Waves of Class 40 would feel without an obvious show of comraeler.

By early spring of 1945, when the Radio Station became a thoroughly male/female integrated Navy Base, ten of the original group of Waves volunteered for transfer with Drafts to other Intercept Stations. Twentysix of the group remained at Bainbridge Island, make/a total of thirtysix of the original group of forty Waves that still belonged, for the duration and six months,to OP-20-G.

If those first Waves helped to “win the war” it was because the career Navy men,whose space the Waves were commanded to invade, helped make it so. By 1946 the Pioneer Waves, the first to live on the hill at the Radio Station and all WWII Waves were gone. All were anxious to get home to begin the business of living their own young civilian lives forty years later again. But–even now,71 their memory remains in thehearts and minds of all who knew “Bainbridge Island’s Pioneer Waves.”

FROM THE AUTHOR – This writing about “Bainbridge Island’s Pioneer Waves” is but an outline of their story. Some of the outline may be at variance with fact since it is a remembrance without benefit of journal. It is from a very different time–forty years ago. Hopefully, others of this first group of Waves and those who followed will tell our association their recollections, be they trivia, sea story or dispute of that written here. There were many laughs and tears during that short time of our lives as Waves and some of those laughs and tears should be told for history’s sake. In conclusion, it must be written that those first Waves selected to pioneer at Bainbridge Island know their efforts were minimal alongside the services of their male peers. However, their being first to be where no Wave had ever been, seems in retrospect to have been a very special achievement.